Stochastic Variational Inference for scalability with SVGP#

One of the main criticisms of Gaussian processes is their scalability to large datasets. In this notebook, we illustrate how to use the state-of-the-art Stochastic Variational Gaussian Process (SVGP) (Hensman, et. al. 2013) to overcome this problem.

[1]:

%matplotlib inline

import itertools

import time

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

import gpflow

from gpflow.ci_utils import reduce_in_tests

plt.style.use("ggplot")

# for reproducibility of this notebook:

rng = np.random.RandomState(123)

tf.random.set_seed(42)

2023-08-09 12:25:38.269483: W tensorflow/compiler/tf2tensorrt/utils/py_utils.cc:38] TF-TRT Warning: Could not find TensorRT

Generating data#

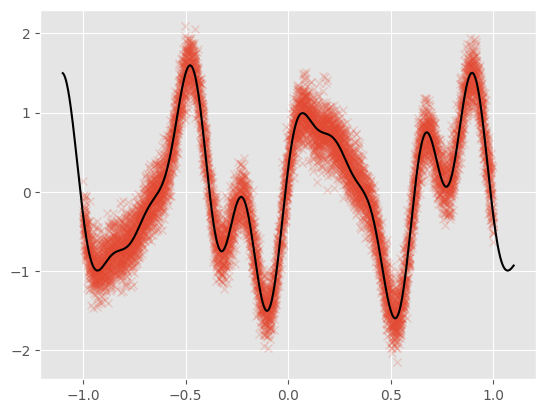

For this notebook example, we generate 10,000 noisy observations from a test function: \begin{equation} f(x) = \sin(3\pi x) + 0.3\cos(9\pi x) + \frac{\sin(7 \pi x)}{2} \end{equation}

[2]:

def func(x):

return (

np.sin(x * 3 * 3.14)

+ 0.3 * np.cos(x * 9 * 3.14)

+ 0.5 * np.sin(x * 7 * 3.14)

)

N = 10000 # Number of training observations

X = rng.rand(N, 1) * 2 - 1 # X values

Y = func(X) + 0.2 * rng.randn(N, 1) # Noisy Y values

data = (X, Y)

We plot the data along with the noiseless generating function:

[3]:

plt.plot(X, Y, "x", alpha=0.2)

Xt = np.linspace(-1.1, 1.1, 1000)[:, None]

Yt = func(Xt)

plt.plot(Xt, Yt, c="k")

Building the model#

The main idea behind SVGP is to approximate the true GP posterior with a GP conditioned on a small set of “inducing” values. This smaller set can be thought of as summarizing the larger dataset. For this example, we will select a set of 50 inducing locations that are initialized from the training dataset:

[4]:

M = 50 # Number of inducing locations

kernel = gpflow.kernels.SquaredExponential()

Z = X[

:M, :

].copy() # Initialize inducing locations to the first M inputs in the dataset

m = gpflow.models.SVGP(kernel, gpflow.likelihoods.Gaussian(), Z, num_data=N)

Likelihood computation: batch vs. minibatch#

First we showcase the model’s performance using the whole dataset to compute the ELBO.

[5]:

elbo = tf.function(m.elbo)

[6]:

# TensorFlow re-traces & compiles a `tf.function`-wrapped method at *every* call if the arguments are numpy arrays instead of tf.Tensors. Hence:

tensor_data = tuple(map(tf.convert_to_tensor, data))

elbo(tensor_data) # run it once to trace & compile

[6]:

<tf.Tensor: shape=(), dtype=float64, numpy=-17730.676725310346>

[7]:

%%timeit

elbo(tensor_data)

23.3 ms ± 2.35 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

We can speed up this calculation by using minibatches of the data. For this example, we use minibatches of size 100.

[8]:

minibatch_size = 100

train_dataset = tf.data.Dataset.from_tensor_slices((X, Y)).repeat().shuffle(N)

train_iter = iter(train_dataset.batch(minibatch_size))

ground_truth = elbo(tensor_data).numpy()

[9]:

%%timeit

elbo(next(train_iter))

1.24 ms ± 498 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

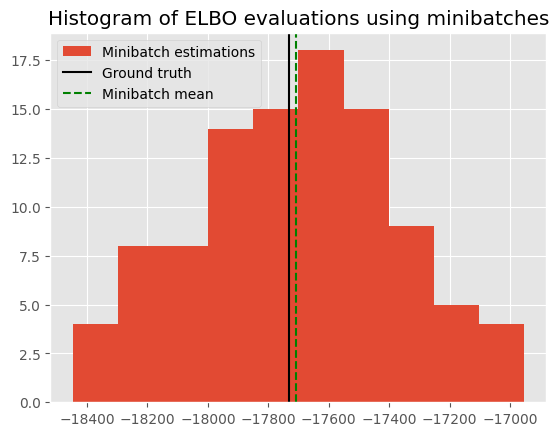

Stochastical estimation of ELBO#

The minibatch estimate should be an unbiased estimator of the ground_truth. Here we show a histogram of the value from different evaluations, together with its mean and the ground truth. The small difference between the mean of the minibatch estimations and the ground truth shows that the minibatch estimator is working as expected.

[10]:

evals = [

elbo(minibatch).numpy() for minibatch in itertools.islice(train_iter, 100)

]

[11]:

plt.hist(evals, label="Minibatch estimations")

plt.axvline(ground_truth, c="k", label="Ground truth")

plt.axvline(np.mean(evals), c="g", ls="--", label="Minibatch mean")

plt.legend()

plt.title("Histogram of ELBO evaluations using minibatches")

print(

"Discrepancy between ground truth and minibatch estimate:",

ground_truth - np.mean(evals),

)

Discrepancy between ground truth and minibatch estimate: -21.802624793072027

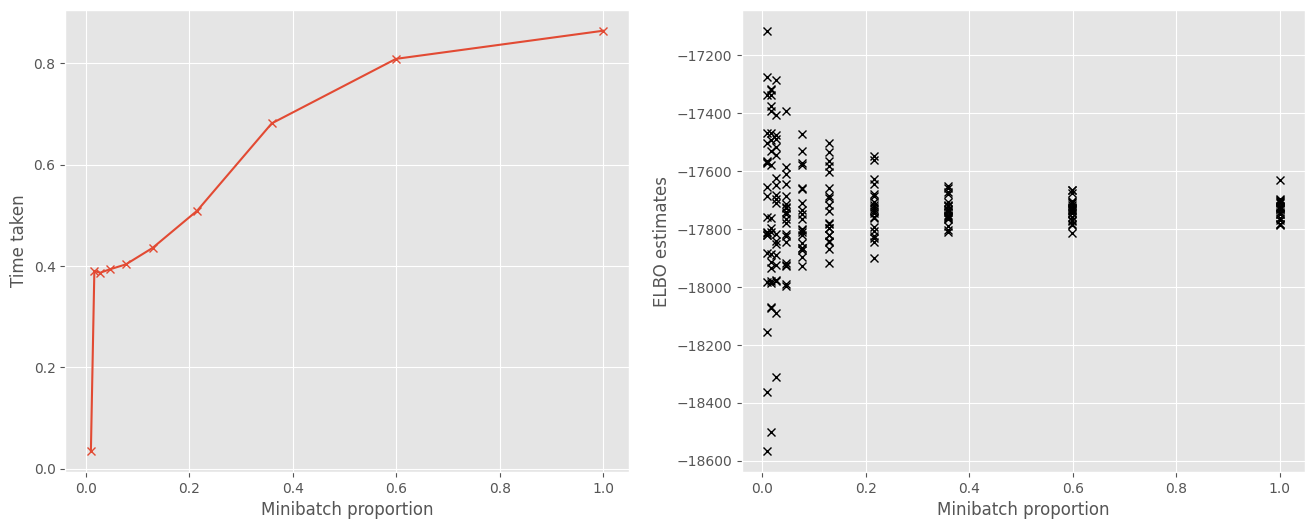

Minibatches speed up computation#

The reason for using minibatches is that it decreases the time needed to make an optimization step, because estimating the objective is computationally cheaper with fewer data points. Here we plot the change in time required with the size of the minibatch. We see that smaller minibatches result in a cheaper estimate of the objective.

[12]:

# Evaluate objective for different minibatch sizes

minibatch_proportions = np.logspace(-2, 0, 10)

times = []

objs = []

for mbp in minibatch_proportions:

batchsize = int(N * mbp)

train_iter = iter(train_dataset.batch(batchsize))

start_time = time.time()

objs.append(

[elbo(minibatch) for minibatch in itertools.islice(train_iter, 20)]

)

times.append(time.time() - start_time)

[13]:

f, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(16, 6))

ax1.plot(minibatch_proportions, times, "x-")

ax1.set_xlabel("Minibatch proportion")

ax1.set_ylabel("Time taken")

ax2.plot(minibatch_proportions, np.array(objs), "kx")

ax2.set_xlabel("Minibatch proportion")

ax2.set_ylabel("ELBO estimates")

[13]:

Text(0, 0.5, 'ELBO estimates')

Running stochastic optimization#

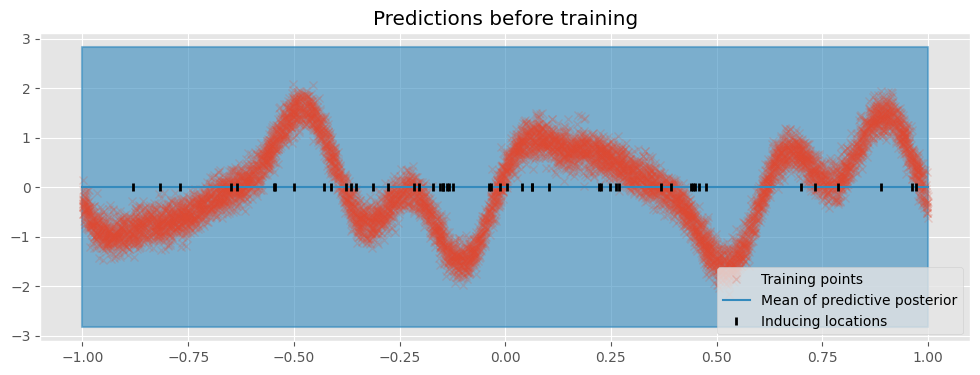

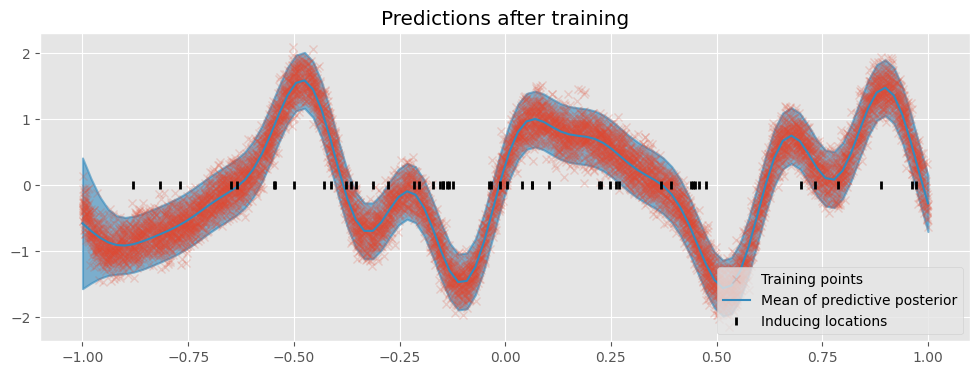

First we create a utility function that plots the model’s predictions:

[14]:

def plot(title=""):

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 4))

plt.title(title)

pX = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)[:, None] # Test locations

pY, pYv = m.predict_y(pX) # Predict Y values at test locations

plt.plot(X, Y, "x", label="Training points", alpha=0.2)

(line,) = plt.plot(pX, pY, lw=1.5, label="Mean of predictive posterior")

col = line.get_color()

plt.fill_between(

pX[:, 0],

(pY - 2 * pYv ** 0.5)[:, 0],

(pY + 2 * pYv ** 0.5)[:, 0],

color=col,

alpha=0.6,

lw=1.5,

)

Z = m.inducing_variable.Z.numpy()

plt.plot(Z, np.zeros_like(Z), "k|", mew=2, label="Inducing locations")

plt.legend(loc="lower right")

plot(title="Predictions before training")

Now we can train our model. For optimizing the ELBO, we use the Adam Optimizer (Kingma and Ba 2015) which is designed for stochastic objective functions. We create a run_adam utility function to perform the optimization.

[15]:

minibatch_size = 100

# We turn off training for inducing point locations

gpflow.set_trainable(m.inducing_variable, False)

def run_adam(model, iterations):

"""

Utility function running the Adam optimizer

:param model: GPflow model

:param interations: number of iterations

"""

# Create an Adam Optimizer action

logf = []

train_iter = iter(train_dataset.batch(minibatch_size))

training_loss = model.training_loss_closure(train_iter, compile=True)

optimizer = tf.optimizers.Adam()

@tf.function

def optimization_step():

optimizer.minimize(training_loss, model.trainable_variables)

for step in range(iterations):

optimization_step()

if step % 10 == 0:

elbo = -training_loss().numpy()

logf.append(elbo)

return logf

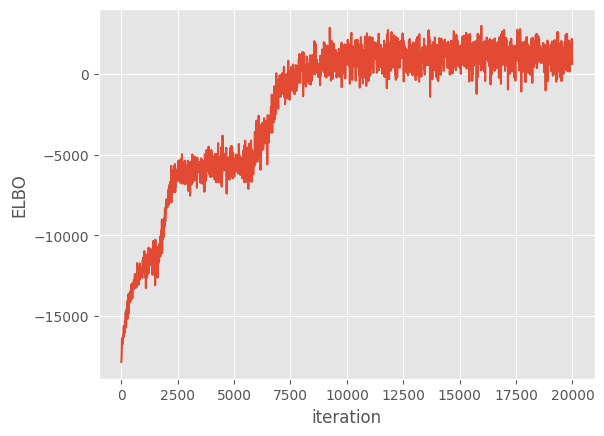

Now we run the optimization loop for 20,000 iterations.

[16]:

maxiter = reduce_in_tests(20000)

logf = run_adam(m, maxiter)

plt.plot(np.arange(maxiter)[::10], logf)

plt.xlabel("iteration")

plt.ylabel("ELBO")

Finally, we plot the model’s predictions.

[17]:

plot("Predictions after training")

Further reading#

Several notebooks expand on this one:

Advanced Sparse GP regression, which goes into deeper detail on sparse Gaussian process methods.

Optimization discussing optimizing GP models.

Natural gradients for optimizing SVGP models efficiently.

References:#

Hensman, James, Nicolo Fusi, and Neil D. Lawrence. “Gaussian processes for big data.” Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (2013).

Kingma, Diederik P., and Jimmy Ba. “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).