MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo)#

GPflow allows you to approximate the posterior over the latent functions of its models (and over the hyperparameters after setting a prior for those) using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC)

[1]:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

import tensorflow_probability as tfp

from multiclass_classification import colors, plot_from_samples

from tensorflow_probability import distributions as tfd

import gpflow

from gpflow import set_trainable

from gpflow.ci_utils import reduce_in_tests

gpflow.config.set_default_float(np.float64)

gpflow.config.set_default_jitter(1e-4)

gpflow.config.set_default_summary_fmt("notebook")

# convert to float64 for tfp to play nicely with gpflow in 64

f64 = gpflow.utilities.to_default_float

tf.random.set_seed(123)

%matplotlib inline

2023-08-09 12:25:32.048403: W tensorflow/compiler/tf2tensorrt/utils/py_utils.cc:38] TF-TRT Warning: Could not find TensorRT

In this notebook, we provide three examples:

Example 1: Sampling hyperparameters in Gaussian process regression

Example 2: Sparse Variational MC applied to the multiclass classification problem

Example 3: Full Bayesian inference for Gaussian process models

Example 1: GP regression#

We first consider the GP regression (with Gaussian noise) for which the marginal likelihood \(p(\mathbf y\,|\,\theta)\) can be computed exactly.

The GPR model parameterized by \(\theta = [\tau]\) is given by \begin{equation} Y_i = f(X_i) + \varepsilon_i \end{equation} where \(f \sim \mathcal{GP}(\mu(.), k(., .))\), and \(\varepsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \tau^2 I)\).

See the Basic (Gaussian likelihood) GP regression model for more details on GPR and for a treatment of the direct likelihood maximization.

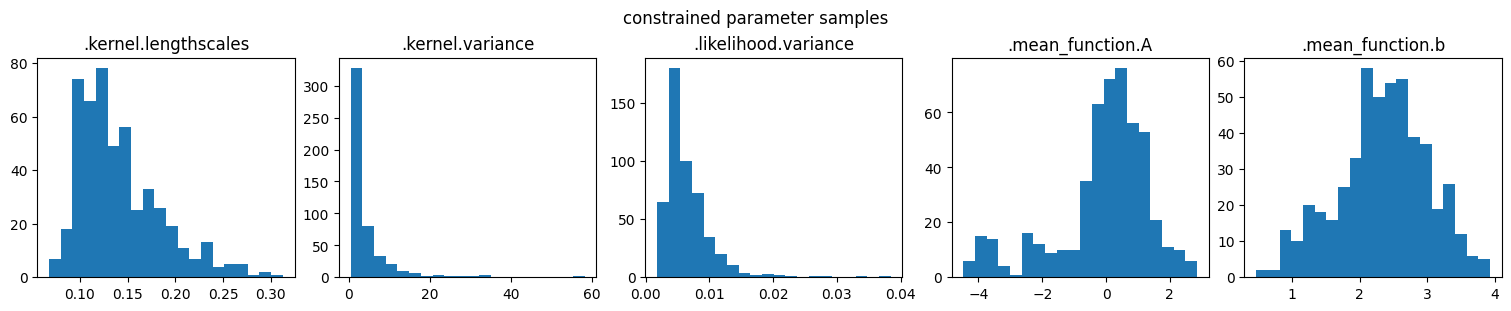

Data for a one-dimensional regression problem#

[2]:

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

N = 15

def synthetic_data(num: int, rng: np.random.RandomState):

X = rng.rand(num, 1)

Y = np.sin(12 * X) + 0.66 * np.cos(25 * X) + rng.randn(num, 1) * 0.1 + 3

return X, Y

data = (X, Y) = synthetic_data(N, rng)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.plot(X, Y, "kx", mew=2)

plt.xlabel("$X$")

plt.ylabel("$Y$")

plt.title("toy data")

plt.show()

MCMC for hyperparameters \(\theta\)#

We now want to sample from the posterior over \(\theta\): \begin{equation} p(\theta|\mathbf{y}) \propto p(\mathbf{y}|\theta)p(\theta) \end{equation}

Firstly, we build the GPR model.

[3]:

kernel = gpflow.kernels.Matern52(lengthscales=0.3)

mean_function = gpflow.mean_functions.Linear(1.0, 0.0)

model = gpflow.models.GPR(data, kernel, mean_function, noise_variance=0.01)

Secondly, we initialize the model to the maximum likelihood solution.

[4]:

optimizer = gpflow.optimizers.Scipy()

optimizer.minimize(model.training_loss, model.trainable_variables)

print(f"log posterior density at optimum: {model.log_posterior_density()}")

log posterior density at optimum: -11.460240793869067

Thirdly, we add priors to the hyperparameters.

[5]:

# tfp.distributions dtype is inferred from parameters - so convert to 64-bit

model.kernel.lengthscales.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

model.kernel.variance.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

model.likelihood.variance.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

model.mean_function.A.prior = tfd.Normal(f64(0.0), f64(10.0))

model.mean_function.b.prior = tfd.Normal(f64(0.0), f64(10.0))

gpflow.utilities.print_summary(model)

| name | class | transform | prior | trainable | shape | dtype | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR.mean_function.A | Parameter | Identity | Normal | True | (1, 1) | float64 | [[-0.79274]] |

| GPR.mean_function.b | Parameter | Identity | Normal | True | () | float64 | 3.37839 |

| GPR.kernel.variance | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 0.85356 |

| GPR.kernel.lengthscales | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 0.07945 |

| GPR.likelihood.variance | Parameter | Softplus + Shift | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 0.01652 |

We now sample from the posterior using HMC.

[6]:

num_burnin_steps = reduce_in_tests(300)

num_samples = reduce_in_tests(1000)

# Note that here we need model.trainable_parameters, not trainable_variables - only parameters can have priors!

hmc_helper = gpflow.optimizers.SamplingHelper(

model.log_posterior_density, model.trainable_parameters

)

hmc = tfp.mcmc.HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

target_log_prob_fn=hmc_helper.target_log_prob_fn,

num_leapfrog_steps=10,

step_size=0.01,

)

adaptive_hmc = tfp.mcmc.SimpleStepSizeAdaptation(

hmc,

num_adaptation_steps=10,

target_accept_prob=f64(0.75),

adaptation_rate=0.1,

)

@tf.function

def run_chain_fn():

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_samples,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=hmc_helper.current_state,

kernel=adaptive_hmc,

trace_fn=lambda _, pkr: pkr.inner_results.is_accepted,

)

samples, traces = run_chain_fn()

parameter_samples = hmc_helper.convert_to_constrained_values(samples)

param_to_name = {

param: name

for name, param in gpflow.utilities.parameter_dict(model).items()

}

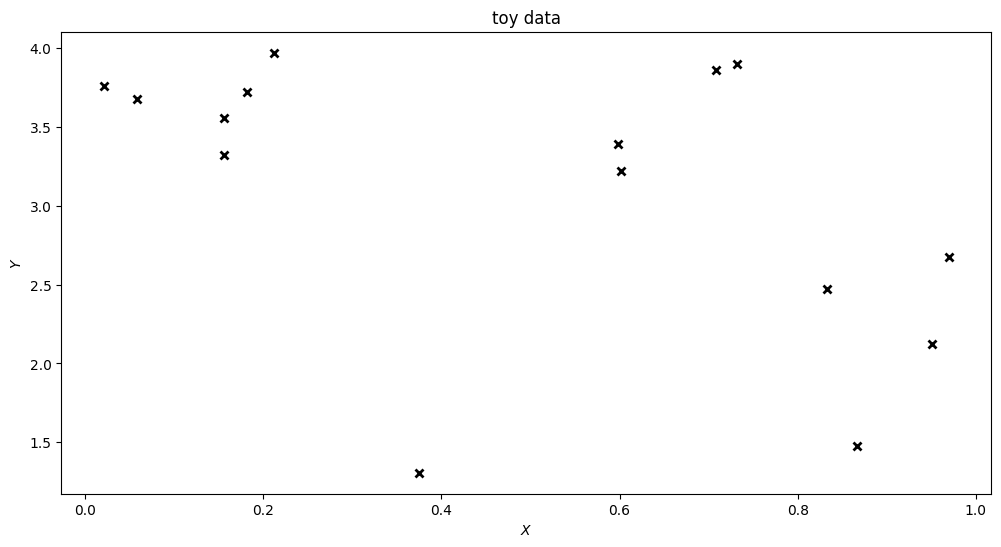

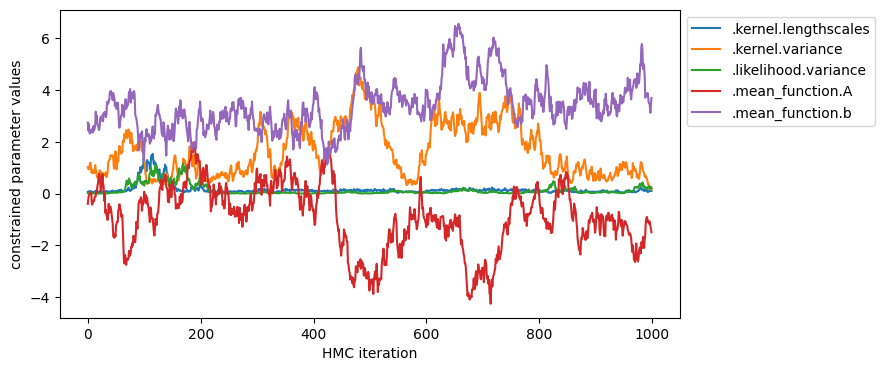

NOTE: All the Hamiltonian MCMC sampling takes place in an unconstrained space (where constrained parameters have been mapped via a bijector to an unconstrained space). This makes the optimization, as required in the gradient step, much easier.

However, we often wish to sample the constrained parameter values, not the unconstrained one. The SamplingHelper helps us convert our unconstrained values to constrained parameter ones.

[7]:

def plot_samples(samples, parameters, y_axis_label):

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

for val, param in zip(samples, parameters):

plt.plot(tf.squeeze(val), label=param_to_name[param])

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.0, 1.0))

plt.xlabel("HMC iteration")

plt.ylabel(y_axis_label)

plot_samples(samples, model.trainable_parameters, "unconstrained values")

plot_samples(

parameter_samples,

model.trainable_parameters,

"constrained parameter values",

)

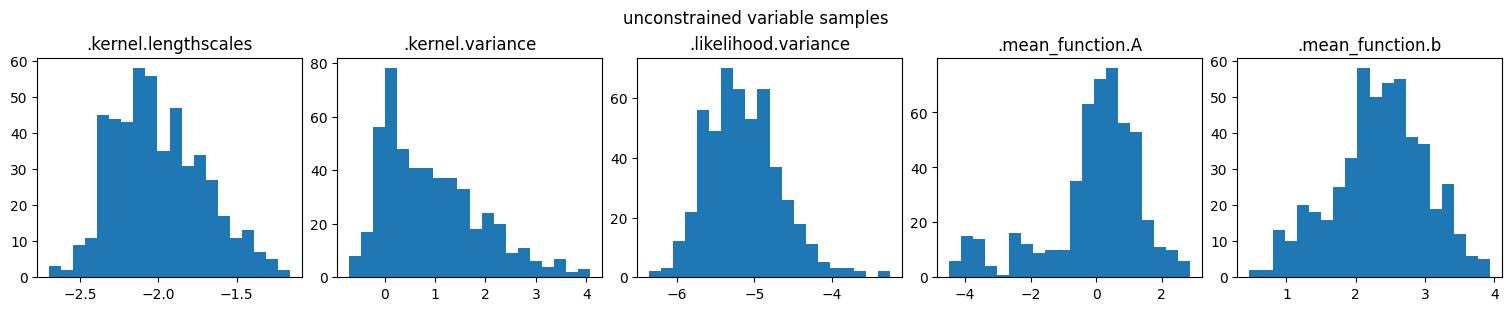

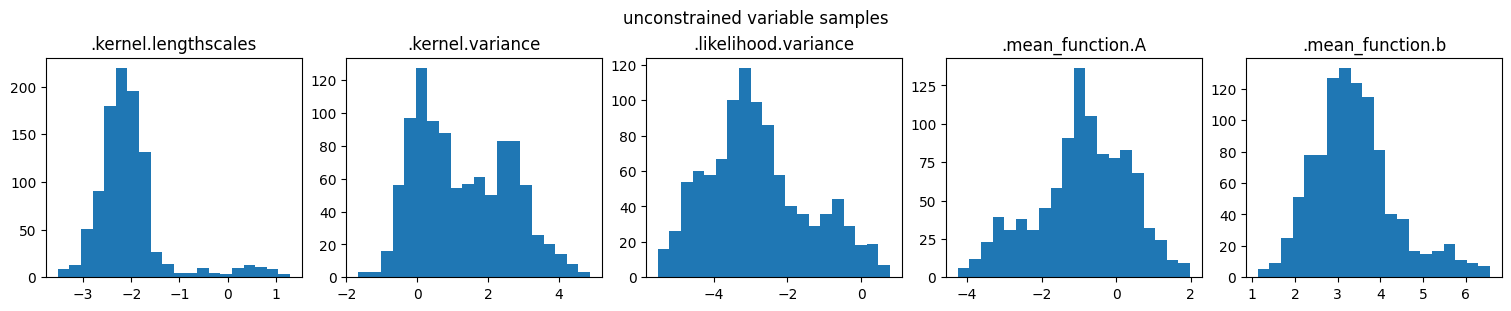

You can also inspect the marginal distribution of samples.

[8]:

def marginal_samples(samples, parameters, y_axis_label):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(

1, len(param_to_name), figsize=(15, 3), constrained_layout=True

)

for ax, val, param in zip(axes, samples, parameters):

ax.hist(np.stack(val).flatten(), bins=20)

ax.set_title(param_to_name[param])

fig.suptitle(y_axis_label)

plt.show()

marginal_samples(

samples, model.trainable_parameters, "unconstrained variable samples"

)

marginal_samples(

parameter_samples,

model.trainable_parameters,

"constrained parameter samples",

)

NOTE: The sampler runs in unconstrained space (so that positive parameters remain positive, and parameters that are not trainable are ignored).

For serious analysis you most certainly want to run the sampler longer, with multiple chains and convergence checks. This will do for illustration though!

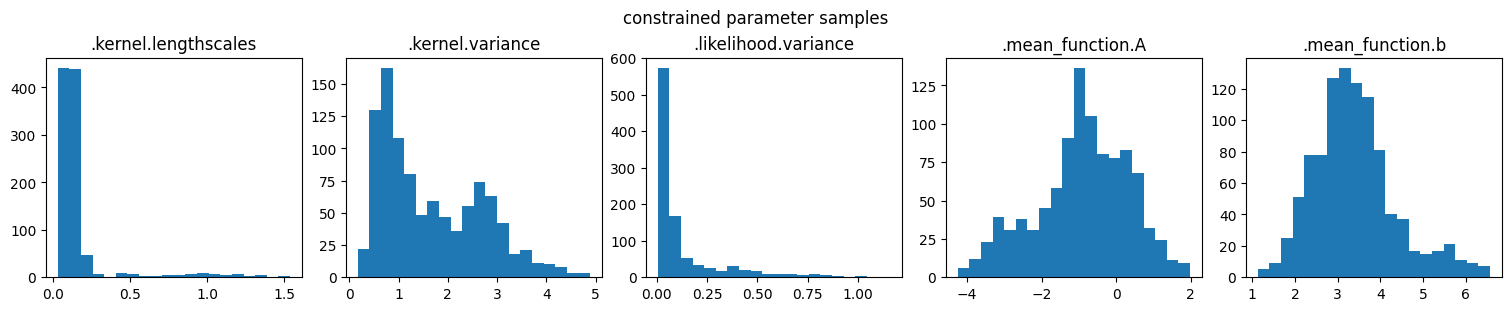

[9]:

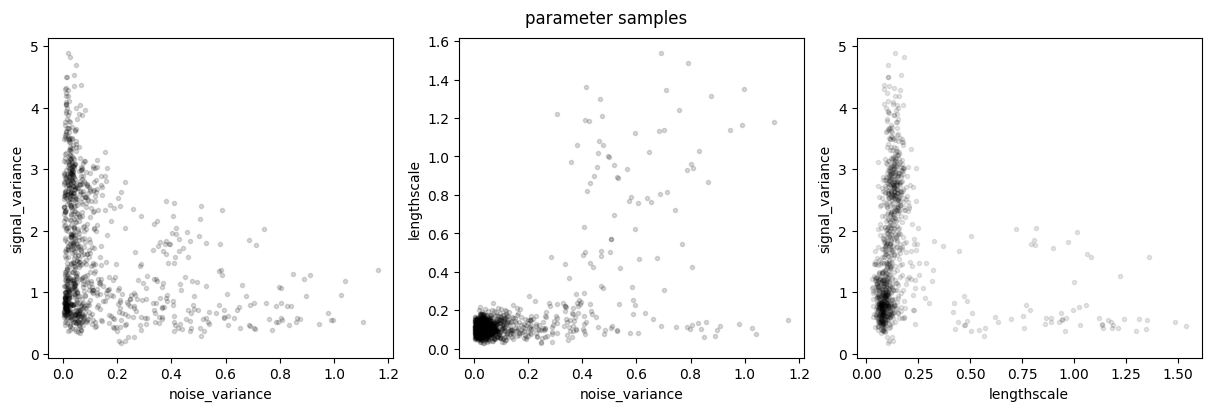

def plot_joint_marginals(samples, parameters, y_axis_label):

name_to_index = {

param_to_name[param]: i for i, param in enumerate(parameters)

}

f, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(12, 4), constrained_layout=True)

axs[0].plot(

samples[name_to_index[".likelihood.variance"]],

samples[name_to_index[".kernel.variance"]],

"k.",

alpha=0.15,

)

axs[0].set_xlabel("noise_variance")

axs[0].set_ylabel("signal_variance")

axs[1].plot(

samples[name_to_index[".likelihood.variance"]],

samples[name_to_index[".kernel.lengthscales"]],

"k.",

alpha=0.15,

)

axs[1].set_xlabel("noise_variance")

axs[1].set_ylabel("lengthscale")

axs[2].plot(

samples[name_to_index[".kernel.lengthscales"]],

samples[name_to_index[".kernel.variance"]],

"k.",

alpha=0.1,

)

axs[2].set_xlabel("lengthscale")

axs[2].set_ylabel("signal_variance")

f.suptitle(y_axis_label)

plt.show()

plot_joint_marginals(

samples, model.trainable_parameters, "unconstrained variable samples"

)

plot_joint_marginals(

parameter_samples, model.trainable_parameters, "parameter samples"

)

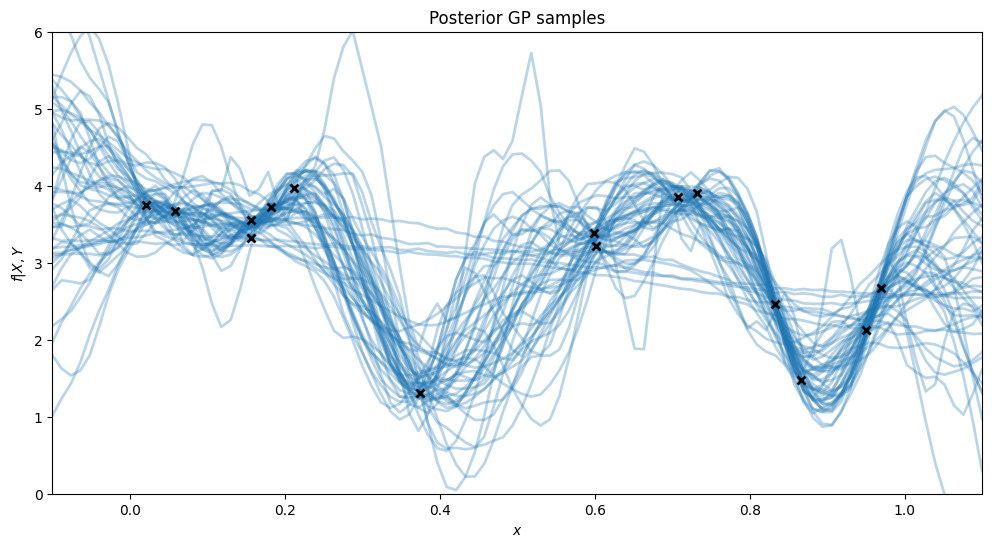

To plot the posterior of predictions, we’ll iterate through the samples and set the model state with each sample. Then, for that state (set of hyperparameters) we’ll draw some samples from the prediction function.

[10]:

# plot the function posterior

xx = np.linspace(-0.1, 1.1, 100)[:, None]

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for i in range(0, num_samples, 20):

for var, var_samples in zip(hmc_helper.current_state, samples):

var.assign(var_samples[i])

f = model.predict_f_samples(xx, 1)

plt.plot(xx, f[0, :, :], "C0", lw=2, alpha=0.3)

plt.plot(X, Y, "kx", mew=2)

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(0, 6)

plt.xlabel("$x$")

plt.ylabel("$f|X,Y$")

plt.title("Posterior GP samples")

plt.show()

This example demonstrates the multi-modality of the true posterior over hyperparameters: the data could be explained both by long lengthscale, small signal variance, and high noise variance, as well as by shorter lengthscale, higher signal variance, and low noise variance.

Example 2: Sparse MC for multiclass classification#

We now consider the multiclass classification problem (see the Multiclass classification notebook). Here the marginal likelihood is not available in closed form. Instead we use a sparse variational approximation where we approximate the posterior for each GP as \(q(f_c) \propto p(f_c|\mathbf{u}_c)q(\mathbf{u}_c)\)

In the standard Sparse Variational GP (SVGP) formulation, \(q(\mathbf{u_c})\) is parameterized as a multivariate Gaussian.

An alternative is to directly sample from the optimal \(q(\mathbf{u}_c)\); this is what Sparse Variational GP using MCMC (SGPMC) does.

We first build a multiclass classification dataset.

[11]:

# Generate data by sampling from SquaredExponential kernel, and classifying with the argmax

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

C, N = 3, 100

X = rng.rand(N, 1)

kernel = gpflow.kernels.SquaredExponential(lengthscales=0.1)

K = kernel.K(X) + np.eye(N) * 1e-6

f = rng.multivariate_normal(mean=np.zeros(N), cov=K, size=(C)).T

Y = np.argmax(f, 1)[:, None].astype(int)

# One-hot encoding

Y_hot = np.zeros((N, C), dtype=bool)

Y_hot[np.arange(N), Y.squeeze(-1)] = 1

data = (X, Y)

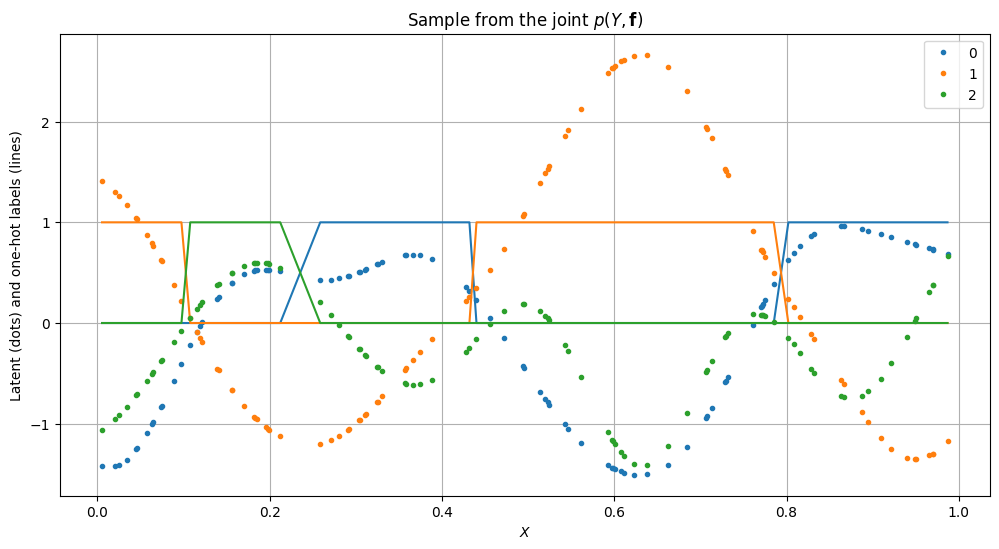

[12]:

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

order = np.argsort(X.flatten())

for c in range(C):

plt.plot(X[order], f[order, c], ".", color=colors[c], label=str(c))

plt.plot(X[order], Y_hot[order, c], "-", color=colors[c])

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel("$X$")

plt.ylabel("Latent (dots) and one-hot labels (lines)")

plt.title("Sample from the joint $p(Y, \mathbf{f})$")

plt.grid()

plt.show()

We then build the SGPMC model.

[13]:

kernel = gpflow.kernels.Matern32(lengthscales=0.1) + gpflow.kernels.White(

variance=0.01

)

model = gpflow.models.SGPMC(

data,

kernel=kernel,

likelihood=gpflow.likelihoods.MultiClass(3),

inducing_variable=X[::5].copy(),

num_latent_gps=3,

)

model.kernel.kernels[0].variance.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

model.kernel.kernels[0].lengthscales.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(2.0), f64(2.0))

set_trainable(model.kernel.kernels[1].variance, False)

gpflow.utilities.print_summary(model)

| name | class | transform | prior | trainable | shape | dtype | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGPMC.kernel.kernels[0].variance | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 1.0 |

| SGPMC.kernel.kernels[0].lengthscales | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 0.1 |

| SGPMC.kernel.kernels[1].variance | Parameter | Softplus | False | () | float64 | 0.01 | |

| SGPMC.likelihood.invlink.epsilon | Parameter | Sigmoid | Beta | False | () | float64 | 0.001 |

| SGPMC.inducing_variable.Z | Parameter | Identity | True | (20, 1) | float64 | [[0.37454... | |

| SGPMC.V | Parameter | Identity | Normal | True | (20, 3) | float64 | [[0., 0., 0.... |

[14]:

# The inducing point locations Z should not be included in the MCMC (see [Hensman et al. (2015)](https://papers.nips.cc/paper/5875-mcmc-for-variationally-sparse-gaussian-processes), hence we set them to non-trainable.

set_trainable(model.inducing_variable, False)

The chain of samples for \(\mathbf{u}_c, \theta\) is initialized at the value maximizing \(p(Y|\mathbf{u}_c, \theta)\).

[15]:

optimizer = gpflow.optimizers.Scipy()

optimizer.minimize(

model.training_loss, model.trainable_variables, options={"maxiter": 20}

)

print(f"log posterior density at optimum: {model.log_posterior_density()}")

log posterior density at optimum: -79.7654902747724

Sampling starts with a ‘burn in’ period.

[16]:

num_burnin_steps = reduce_in_tests(100)

num_samples = reduce_in_tests(500)

# Note that here we need model.trainable_parameters, not trainable_variables - only parameters can have priors!

hmc_helper = gpflow.optimizers.SamplingHelper(

model.log_posterior_density, model.trainable_parameters

)

hmc = tfp.mcmc.HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

target_log_prob_fn=hmc_helper.target_log_prob_fn,

num_leapfrog_steps=10,

step_size=0.01,

)

adaptive_hmc = tfp.mcmc.SimpleStepSizeAdaptation(

hmc,

num_adaptation_steps=10,

target_accept_prob=f64(0.75),

adaptation_rate=0.1,

)

@tf.function

def run_chain_fn():

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_samples,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=hmc_helper.current_state,

kernel=adaptive_hmc,

trace_fn=lambda _, pkr: pkr.inner_results.is_accepted,

)

samples, _ = run_chain_fn()

constrained_samples = hmc_helper.convert_to_constrained_values(samples)

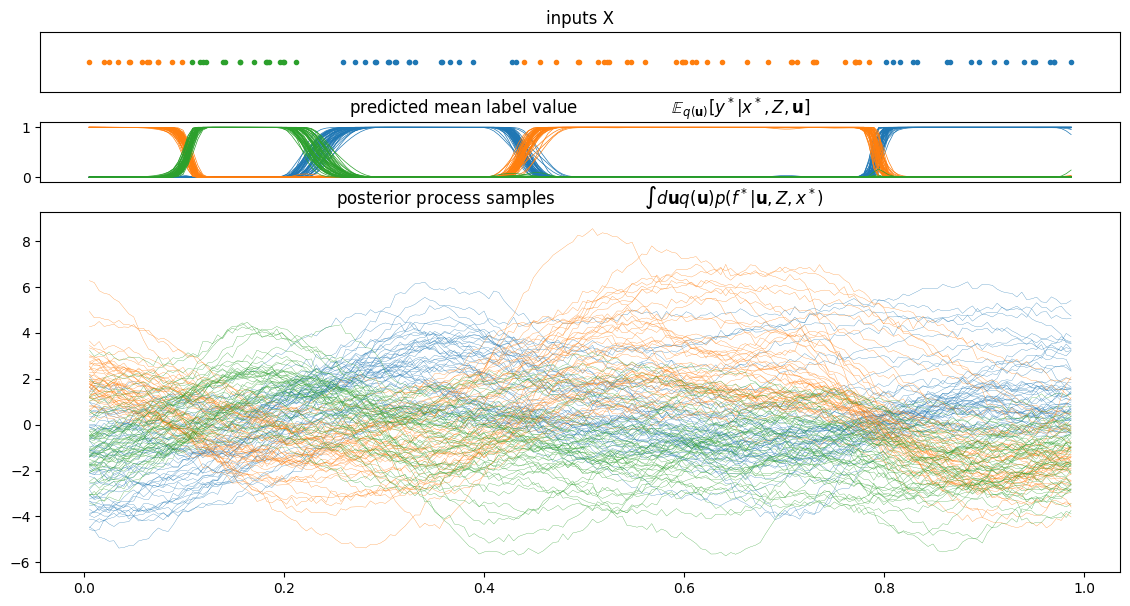

Statistics of the posterior samples can now be reported.

[17]:

plot_from_samples(

model, X, Y, model.trainable_parameters, constrained_samples, thin=10

)

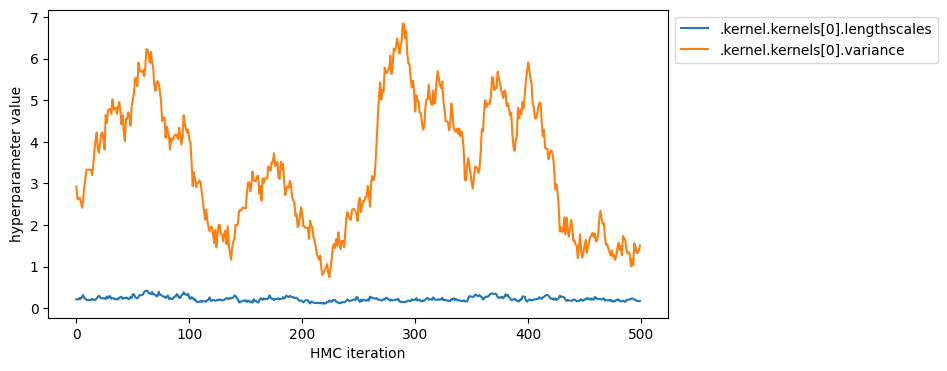

You can also display the sequence of sampled hyperparameters.

[18]:

param_to_name = {

param: name

for name, param in gpflow.utilities.parameter_dict(model).items()

}

name_to_index = {

param_to_name[param]: i

for i, param in enumerate(model.trainable_parameters)

}

hyperparameters = [

".kernel.kernels[0].lengthscales",

".kernel.kernels[0].variance",

]

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

for param_name in hyperparameters:

plt.plot(constrained_samples[name_to_index[param_name]], label=param_name)

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.0, 1.0))

plt.xlabel("HMC iteration")

plt.ylabel("hyperparameter value")

Example 3: Fully Bayesian inference for generalized GP models with HMC#

You can construct very flexible models with Gaussian processes by combining them with different likelihoods (sometimes called ‘families’ in the GLM literature). This makes inference of the GP intractable because the likelihoods are not generally conjugate to the Gaussian process. The general form of the model is \begin{align} \theta &\sim p(\theta) \\ f &\sim \mathcal {GP}(m(x; \theta),\, k(x, x'; \theta)) \\ y_i &\sim p(y | g(f(x_i))\,. \end{align}

To perform inference in this model, we’ll run MCMC using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) over the function values and the parameters \(\theta\) jointly. The key to an effective scheme is rotation of the field using the Cholesky decomposition. We write:

\begin{align} \theta &\sim p(\theta) \\ v &\sim \mathcal {N}(0,\, I) \\ LL^\top &= K \\ f &= m + Lv \\ y_i &\sim p(y | g(f(x_i))\,. \end{align}

Joint HMC over \(v\) and the function values is not widely adopted in the literature because of the difficulty in differentiating \(LL^\top=K\). We’ve made this derivative available in TensorFlow, and so application of HMC is relatively straightforward.

Exponential Regression#

We consider an exponential regression model: \begin{align} \theta &\sim p(\theta) \\ f &\sim \mathcal {GP}(0, k(x, x'; \theta)) \\ f_i &= f(x_i) \\ y_i &\sim \mathcal {Exp} (e^{f_i}) \end{align}

We’ll use MCMC to deal with both the kernel parameters \(\theta\) and the latent function values \(f\). Firstly, generate a data set.

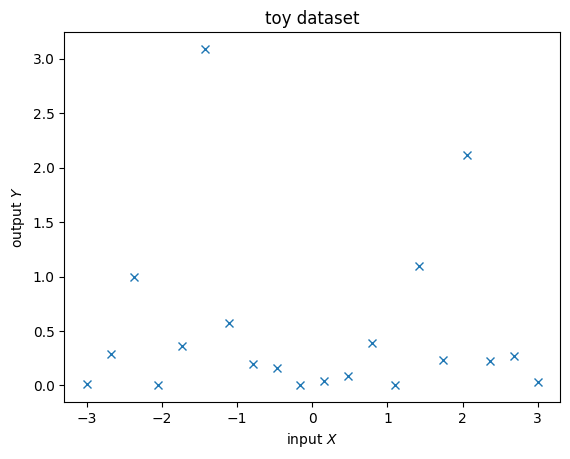

[19]:

rng = np.random.RandomState(14)

X = np.linspace(-3, 3, 20)

Y = rng.exponential(np.sin(X) ** 2)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(X, Y, "x")

plt.xlabel("input $X$")

plt.ylabel("output $Y$")

plt.title("toy dataset")

plt.show()

data = (X[:, None], Y[:, None])

GPflow’s model for fully-Bayesian MCMC is called GPMC. It’s constructed like any other model, but contains a parameter V which represents the centered values of the function.

[20]:

kernel = gpflow.kernels.Matern32() + gpflow.kernels.Constant()

likelihood = gpflow.likelihoods.Exponential()

model = gpflow.models.GPMC(data, kernel, likelihood)

The V parameter already has a prior applied. We’ll add priors to the parameters also (these are rather arbitrary, for illustration).

[21]:

model.kernel.kernels[0].lengthscales.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

model.kernel.kernels[0].variance.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

model.kernel.kernels[1].variance.prior = tfd.Gamma(f64(1.0), f64(1.0))

gpflow.utilities.print_summary(model)

| name | class | transform | prior | trainable | shape | dtype | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPMC.kernel.kernels[0].variance | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 1.0 |

| GPMC.kernel.kernels[0].lengthscales | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 1.0 |

| GPMC.kernel.kernels[1].variance | Parameter | Softplus | Gamma | True | () | float64 | 1.0 |

| GPMC.V | Parameter | Identity | Normal | True | (20, 1) | float64 | [[0.... |

Running HMC is pretty similar to optimizing a model. GPflow builds on top of tensorflow_probability’s mcmc module and provides a SamplingHelper class to make interfacing easier.

We initialize HMC at the maximum a posteriori parameter values of the model.

[22]:

optimizer = gpflow.optimizers.Scipy()

maxiter = reduce_in_tests(3000)

optimizer.minimize(

model.training_loss,

model.trainable_variables,

options=dict(maxiter=maxiter),

)

# We can now start HMC near maximum a posteriori (MAP)

We then run the sampler,

[23]:

num_burnin_steps = reduce_in_tests(600)

num_samples = reduce_in_tests(1000)

# Note that here we need model.trainable_parameters, not trainable_variables - only parameters can have priors!

hmc_helper = gpflow.optimizers.SamplingHelper(

model.log_posterior_density, model.trainable_parameters

)

hmc = tfp.mcmc.HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

target_log_prob_fn=hmc_helper.target_log_prob_fn,

num_leapfrog_steps=10,

step_size=0.01,

)

adaptive_hmc = tfp.mcmc.SimpleStepSizeAdaptation(

hmc,

num_adaptation_steps=10,

target_accept_prob=f64(0.75),

adaptation_rate=0.1,

)

@tf.function

def run_chain_fn():

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_samples,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=hmc_helper.current_state,

kernel=adaptive_hmc,

trace_fn=lambda _, pkr: pkr.inner_results.is_accepted,

)

samples, _ = run_chain_fn()

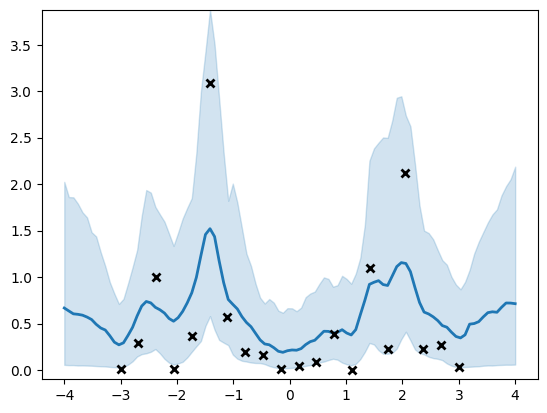

And compute the posterior prediction on a grid for plotting purposes.

[24]:

Xtest = np.linspace(-4, 4, 100)[:, None]

f_samples = []

for i in range(num_samples):

# Note that hmc_helper.current_state contains the unconstrained variables

for var, var_samples in zip(hmc_helper.current_state, samples):

var.assign(var_samples[i])

f = model.predict_f_samples(Xtest, 5)

f_samples.append(f)

f_samples = np.vstack(f_samples)

[25]:

rate_samples = np.exp(f_samples[:, :, 0])

(line,) = plt.plot(Xtest, np.mean(rate_samples, 0), lw=2)

plt.fill_between(

Xtest[:, 0],

np.percentile(rate_samples, 5, axis=0),

np.percentile(rate_samples, 95, axis=0),

color=line.get_color(),

alpha=0.2,

)

plt.plot(X, Y, "kx", mew=2)

plt.ylim(-0.1, np.max(np.percentile(rate_samples, 95, axis=0)))

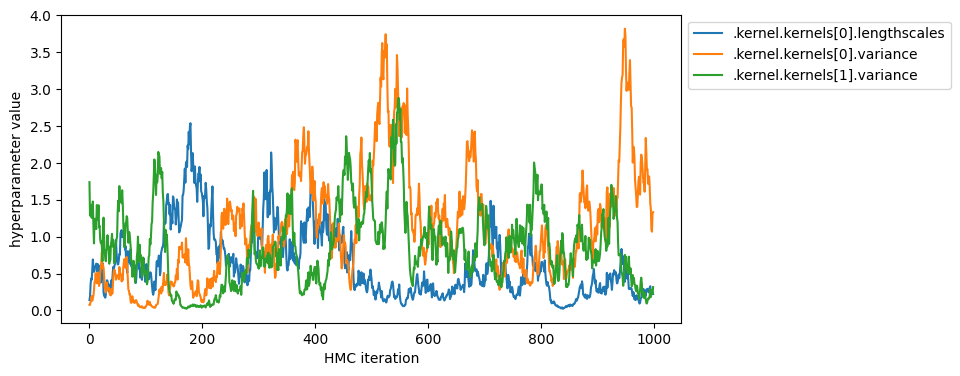

You can also display the sequence of sampled hyperparameters.

[26]:

parameter_samples = hmc_helper.convert_to_constrained_values(samples)

param_to_name = {

param: name

for name, param in gpflow.utilities.parameter_dict(model).items()

}

name_to_index = {

param_to_name[param]: i

for i, param in enumerate(model.trainable_parameters)

}

hyperparameters = [

".kernel.kernels[0].lengthscales",

".kernel.kernels[0].variance",

".kernel.kernels[1].variance",

]

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

for param_name in hyperparameters:

plt.plot(parameter_samples[name_to_index[param_name]], label=param_name)

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.0, 1.0))

plt.xlabel("HMC iteration")

plt.ylabel("hyperparameter value")

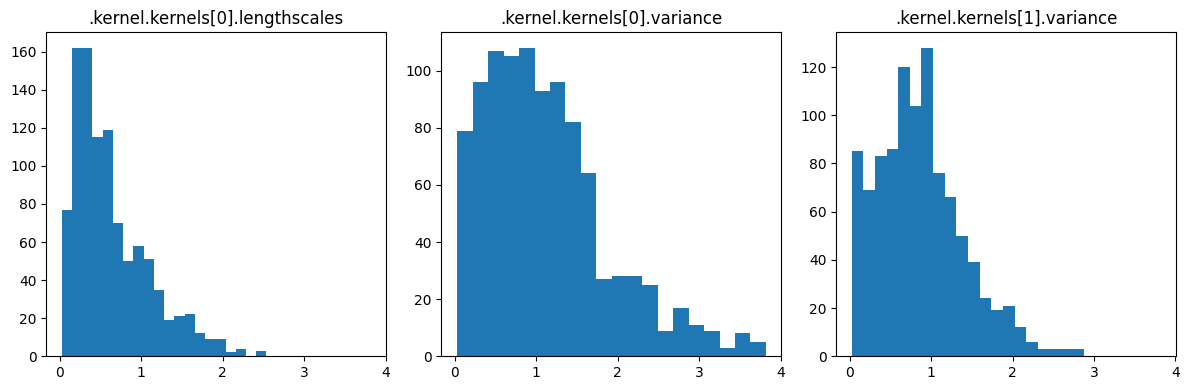

You can also inspect the marginal of the posterior samples.

[27]:

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, len(hyperparameters), sharex=True, figsize=(12, 4))

for ax, param_name in zip(axes, hyperparameters):

ax.hist(parameter_samples[name_to_index[param_name]], bins=20)

ax.set_title(param_name)

plt.tight_layout()

Prior on constrained and unconstrained parameters#

GPflow’s Parameter class provides options for setting a prior. Parameter wraps a constrained tensor and provides computation of the gradient with respect to unconstrained transformation of that tensor. The user can set a prior either in constrained space or unconstrained space.

By default, the prior for the Parameter is set on the constrained space. To explicitly set the space on which the prior is defined, use the prior_on keyword argument:

[28]:

prior_distribution = tfd.Normal(f64(0.0), f64(1.0))

gpflow.Parameter(1.0, prior_on="unconstrained", prior=prior_distribution)

gpflow.Parameter(1.0, prior_on="constrained", prior=prior_distribution)

gpflow.optimizers.SamplingHelper makes sure that the prior density correctly reflects the space in which the prior is defined.

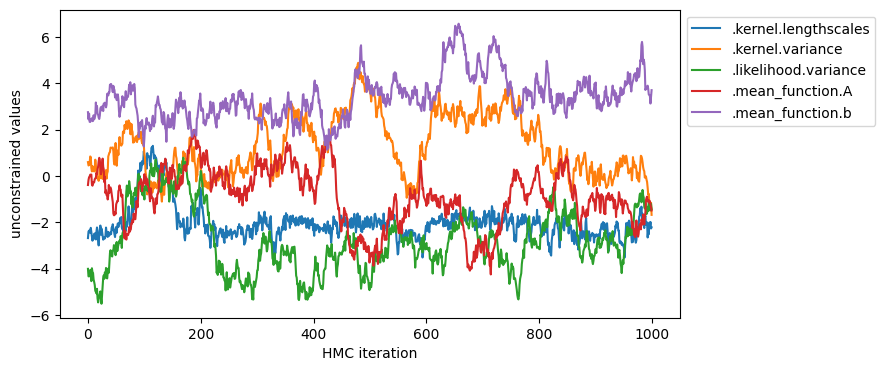

Below we repeat the same experiment as before, but with some priors defined in the unconstrained space. We are using the exponential transform to ensure positivity of the kernel parameters (set_default_positive_bijector("exp")), so a log-normal prior on a constrained parameter corresponds to a normal prior on the unconstrained space:

[29]:

gpflow.config.set_default_positive_bijector("exp")

gpflow.config.set_default_positive_minimum(1e-6)

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

data = synthetic_data(30, rng)

kernel = gpflow.kernels.Matern52(lengthscales=0.3)

meanf = gpflow.mean_functions.Linear(1.0, 0.0)

model = gpflow.models.GPR(data, kernel, meanf)

model.likelihood.variance.assign(0.01)

mu = f64(0.0)

std = f64(4.0)

one = f64(1.0)

model.kernel.lengthscales.prior_on = "unconstrained"

model.kernel.lengthscales.prior = tfd.Normal(mu, std)

model.kernel.variance.prior_on = "unconstrained"

model.kernel.variance.prior = tfd.Normal(mu, std)

model.likelihood.variance.prior_on = "unconstrained"

model.likelihood.variance.prior = tfd.Normal(mu, std)

model.mean_function.A.prior_on = "constrained"

model.mean_function.A.prior = tfd.Normal(mu, std)

model.mean_function.b.prior_on = "constrained"

model.mean_function.b.prior = tfd.Normal(mu, std)

model.kernel.lengthscales.prior_on

[29]:

<PriorOn.UNCONSTRAINED: 'unconstrained'>

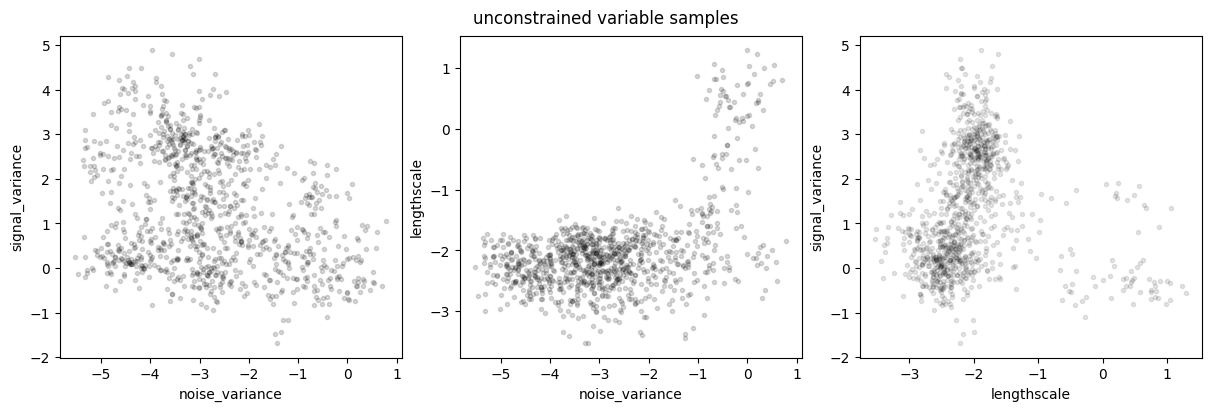

Let’s run HMC and plot chain traces:

[30]:

num_burnin_steps = reduce_in_tests(300)

num_samples = reduce_in_tests(500)

hmc_helper = gpflow.optimizers.SamplingHelper(

model.log_posterior_density, model.trainable_parameters

)

hmc = tfp.mcmc.HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

target_log_prob_fn=hmc_helper.target_log_prob_fn,

num_leapfrog_steps=10,

step_size=0.01,

)

adaptive_hmc = tfp.mcmc.SimpleStepSizeAdaptation(

hmc,

num_adaptation_steps=10,

target_accept_prob=f64(0.75),

adaptation_rate=0.1,

)

@tf.function

def run_chain_fn_unconstrained():

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_samples,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=hmc_helper.current_state,

kernel=adaptive_hmc,

trace_fn=lambda _, pkr: pkr.inner_results.is_accepted,

)

samples, traces = run_chain_fn_unconstrained()

parameter_samples = hmc_helper.convert_to_constrained_values(samples)

param_to_name = {

param: name

for name, param in gpflow.utilities.parameter_dict(model).items()

}

marginal_samples(

samples, model.trainable_parameters, "unconstrained variable samples"

)

marginal_samples(

parameter_samples,

model.trainable_parameters,

"constrained parameter samples",

)